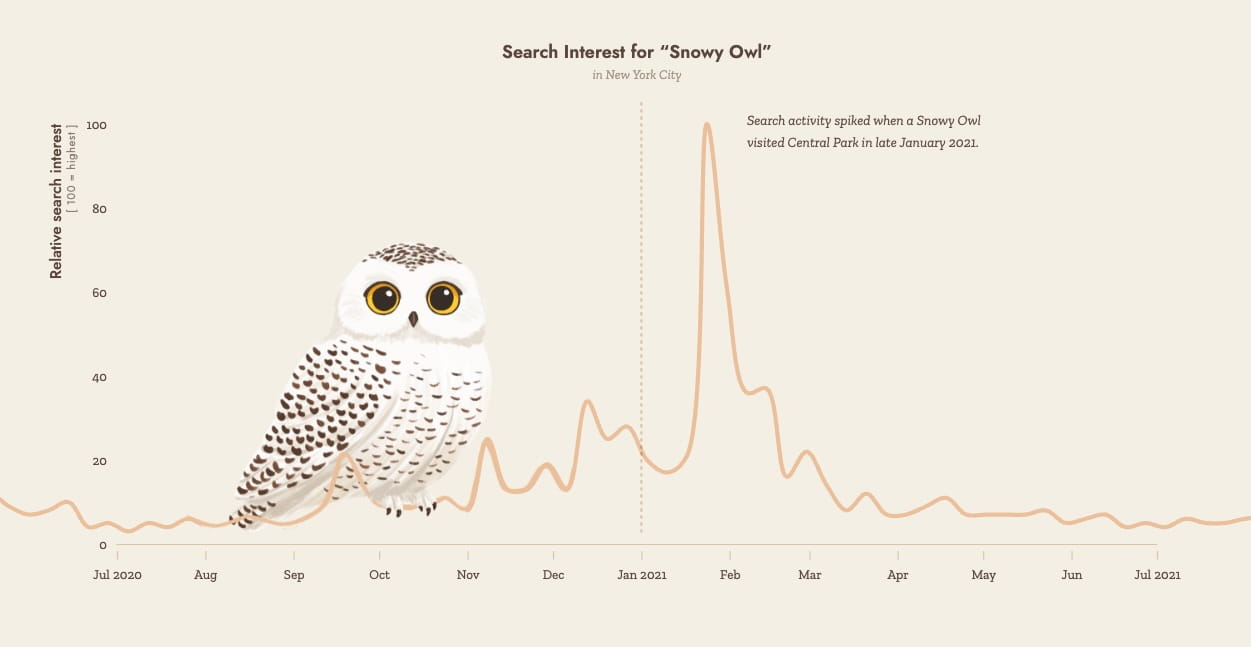

Winter months are dreary in New York City, but perhaps none so much as January 2021. Cold air and gray clouds blew between the skyscrapers as the world below remained stuck in the pandemic’s icy grip.

But that month, a small corner of the city briefly came alive when a majestic Snowy Owl appeared in Central Park. Bird fanatics and dozens of other intrigued New Yorkers ventured out of their homes, hoping to catch a glimpse.

As word spread, so, too, did people’s curiosity. In New York City, Google searches for the term Snowy Owl spiked as residents wanted to learn about the species — and how one ended up in their backyard. New York’s Snowy Owl was as much a story about one special bird as the humans who took notice of it.

Chart: Snowy Owl Search Interest

A line chart showing the relative Google search interest for "Snowy Owl" in New York. The interest spikes dramatically in January 2021, reaching a peak of 100, coinciding with the appearance of a Snowy Owl in Central Park. Prior to this event, interest was negligible.

Google search data, which is available through the company’s Google Trends database, can show us which birds capture our attention.

Google Trends categorizes search terms based on their meaning. For instance, cardinals, orioles, ducks and falcons could refer to either sports teams or birds, but Google generally distinguishes between the helmeted kind and the winged kind. (This story will point out the rare instances when meanings get muddled.)

As you scroll through the following interactive graphics, you’ll get a glimpse at roughly 700 North American and Hawaiian species and learn about why some of them make us fall in love. Let’s see what search trends tell us about our relationship with our feathered friends.

Part One

I Am Not a Bird Person

It’s kind of intimidating how many birds there are. Not in a menacing, Alfred Hitchcock sense, but in an awe-inspiring sense. If you’ve ever cracked open a birding guidebook, you may have felt overwhelmed by the staggering variety of shapes and colors.

The thing is, even if you don’t consider yourself a “bird person,” you inherently know enough about birds to describe an unfamiliar species in familiar terms. You might characterize a loon as a duck, or a falcon as a hawk. These shortcuts stem from a recognition of similar shapes, environments and behaviors — even if the unfamiliar bird actually belongs to an entirely separate family. That’s why there are more searches for general bird terms, like duck or hawk (or owl or parrot) than for individual species names.

Within the nest below you can find the most Googled birds in the U.S. over the last five years, based on their general “type.”

Visualization: Most Searched Bird Groups

A circular visualization depicting a bird nest containing eggs. Each egg represents a general bird type (like "Hawk", "Eagle", "Duck"). The size of the egg corresponds to its search popularity. The largest eggs are Hawk, Eagle, and Duck, indicating they are the most searched bird terms. Other visible groups include Owl, Parrot, and Falcon.

Ornithologists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology know that humans use clues to identify birds, which is why their online guide, All About Birds, is searchable by location, keywords and even bird shape. As of October 2025, the All About Birds database had grouped over 700 species into 76 general “types” of birds. These “type” categories are the basis for the Google search terms shown in the nest. The rankings reflect average search interest over the past five years at the U.S. national and state levels.

Countrywide, two birds of prey — hawk and eagle — get the most searches. They each take the No. 1 search spot in a dozen states. Duck comes in third nationally, but it has the broadest state-level interest, taking the top spot in 17 states.

For many people, bird identification doesn’t stretch much beyond these general bird categories. But being a “birder,” a “birdwatcher,” or a “bird person” doesn’t require encyclopedic knowledge of bird names. In fact, it doesn’t require much of anything. There’s a brand of birding that fosters a gentle approach of simply noticing and observing birds for nothing other than the joy of doing so — no deeper knowledge or superzoom cameras required.

Over the last decade, birding has become a more inclusive activity, with organizations popping up around the country to cater to people of all backgrounds and abilities. The mission of these groups is to cultivate communities of birders who don’t necessarily identify with the hard-core, rare-bird-chasing crowd.

But once you begin to notice birds, there’s a good chance you’ll see one that changes everything.

Part Two

The Spark Bird

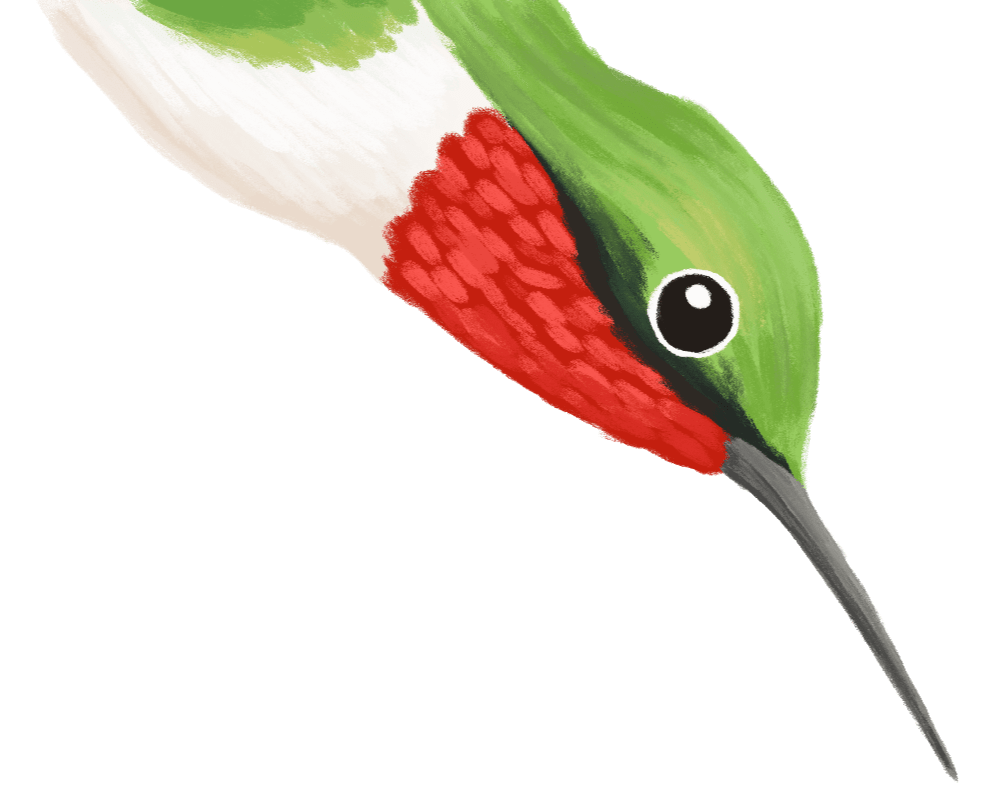

It might seem challenging to get from “duck” to the more specific Green-winged Teal. But the identification process starts with a simple step: caring to know a bird’s name in the first place. Often, this happens after a particular encounter with a very special bird — a so-called “spark bird.”

A spark bird is the catalyst to wanting to discover more. Every spark bird is personal because people are moved by birds for different reasons. Sometimes it’s the flash of color or striking patterns of the feathers. Other times it’s a mesmerizing behavior or an unexpectedly close encounter. But whatever the case, a spark bird becomes the gateway to identifying other birds. Here’s one way to think about their role in that learning process:

Interactive: Bird Shapes to Species

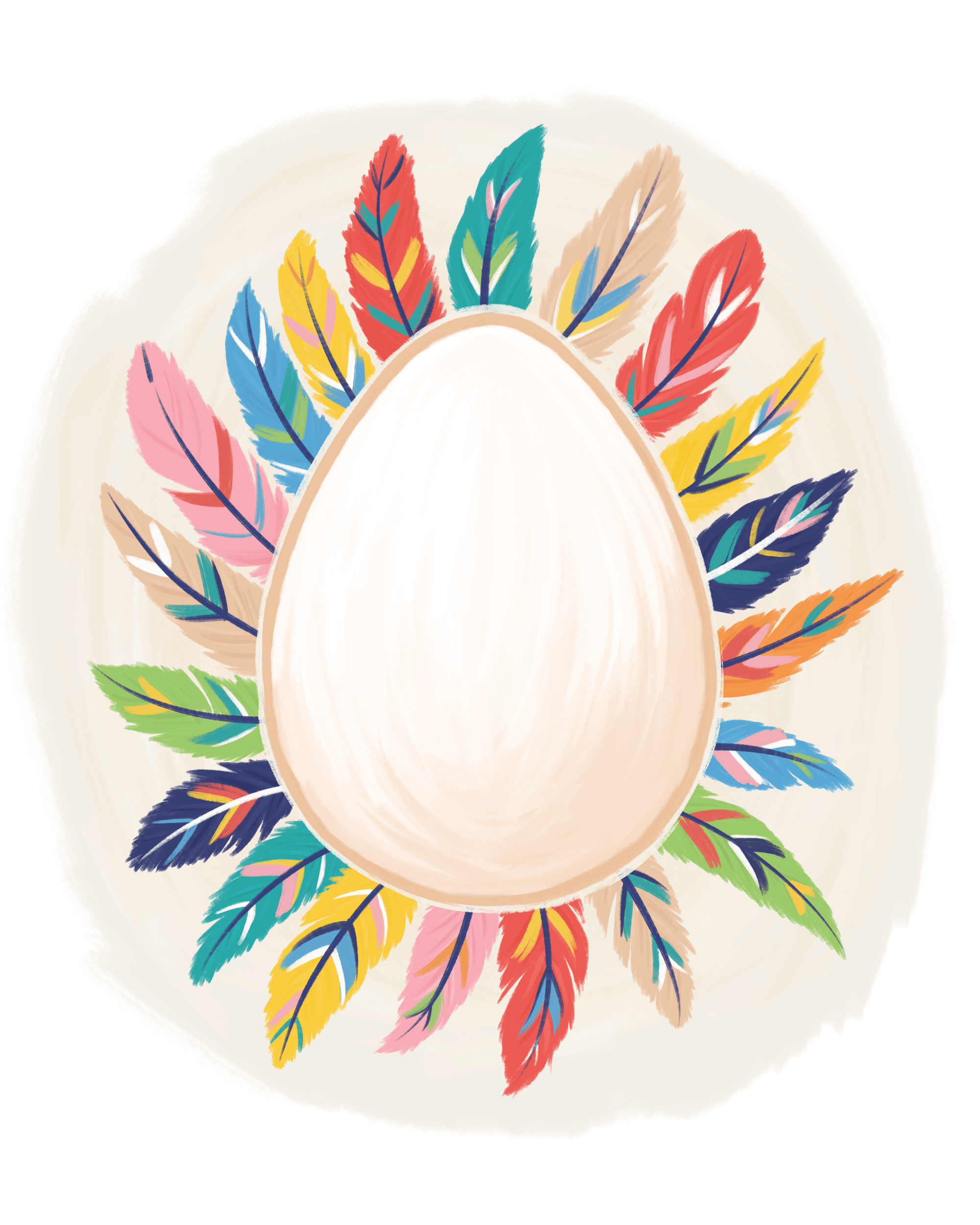

An interactive chart exploring bird categorization. It starts as a single large egg representing all American birds. As you scroll, it subdivides into 25 general shapes (like "Duck-like" or "Hawk-like"), then further into 76 distinct types, and finally reveals individual species. The visualization highlights that while there are hundreds of species, only 98 have significant Google search interest, with most user interest concentrated on general terms rather than specific species.

American birds

Let’s say this egg represents all of the birds in North America and the Hawaiian Islands. It can be divided into roughly 700 different species.

One of them just stole your heart. It’s your spark bird.

Bird shapes

You don’t yet know the name of your spark bird, but you can recognize its general shape, like a hawk or a duck or a hummingbird. North American birds can be categorized into 25 shapes, according to the All About Birds classification.

Bird types

Those shapes can then be split into 76 types. For instance, geese and swans have some resemblance to ducks, but they are different enough to have their own subgroups. Names may start to sound obscure at this point —like jaegers, pipits and shrikes — but it’s all part of narrowing your search.

Use two fingers to pinch and zoom into the egg. Also use two fingers to pan in any direction.

Bird species

By exploring the areas of the egg that seem close to your spark bird, you’ll soon identify it.

Hover overSelect any bird in the egg to see more information. Click on a bird to see its full profile in the All About Birds guide (opens in a new tab).

What we search for

Once you have found your spark bird, you may wonder if other people are curious about this amazing bird as well.

As striking as your spark bird may be, there is a good chance it’s not getting a lot of interest from the general public — and especially if it’s rarely spotted in the U.S. (like the Flame-colored Tanager), well camouflaged (like the American Bittern), or hard to access (like the Black Rosy-Finch).

In fact, Google search data shows that only 98 bird species have significant search interest across the U.S. An additional 11 birds have search interest in at least one state. Here’s a look at the egg with those high interest birds highlighted in various colors according to their type.

Birds with measurable Google search interest

Solid | Popular across the US

Striped | Popular in at least one state

The colorful areas of the egg spotlight the birds that pique our interest. For instance, we frequently Google species of hawks, owls and other raptors. We also can’t get enough of the woodpeckers. It figures that we, collectively, are curious about these birds given their fascinating abilities and behaviors.

Grouping birds, either by shape or family, is both an art and a science. Whether a species belongs with one group versus another can be a matter of debate.

We also often search for species of game birds and ducks, particularly the hunting breeds like the Northern Pintail and the Wood Duck. We love Northern Cardinals and Blue Jays, with their eye-catching shades of reds and blues. And we gravitate to the elegant silhouettes of Great Egrets and Great Blue Herons.

On the other hand, it seems we don’t tend to search for species of gulls, terns and seabirds. Perhaps this is because more than half of the U.S. population doesn’t live near a shore.

Furthermore, seabirds can be tricky to distinguish, so we are less likely to search for their species names and instead fall back on general labels like seagull. The same case could be made for the myriad of little brown birds like sparrows, warblers and chickadees.

Part Three

Find a Bird, Share a Bird

The more effort you put into researching a bird’s name, the more satisfaction when you finally identify it.

But the digital age is all about instant gratification. Social media allows us to share photos of birds and tap into online communities for identification help. A growing number of apps including Merlin Bird ID (created by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology), Seek (by iNaturalist) and Birda use photo identification technology and artificial intelligence to instantly suggest possible bird species based on photos, even if they’re blurry. Merlin takes things a step further, offering possible identifications based on birdsong recordings.

Oftentimes, though, we don’t have our phones at the ready, especially during spontaneous bird encounters. In those cases, we need to rely on our memory of a bird in order to identify it. Reaching out to the birder community (in person or on digital forums) can help narrow the search. So, too, can chatbots, like this one from Google’s Gemini:

"Spark Bird" AI Assistant

Digital tools don’t just benefit us; they also benefit the birds. The public eBird database, run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, has been recognized as the largest citizen science birdwatching project in the world, surpassing 2 billion bird observations in 2025. When you enter your bird sighting into the eBird app, you contribute to an enormous repository of information about population trends, migration patterns and habitat use. All of this information can help scientists identify threats to the birds and shape conservation policy.

Part Four

What We See — and What We Don’t

Snowy Owls are rare. The estimated 15,000 that exist in North America stick mainly to Alaska and Canada, where they breed, and don’t often visit the lower 48 states. On the rarest of occasions, one may end up in Central Park.

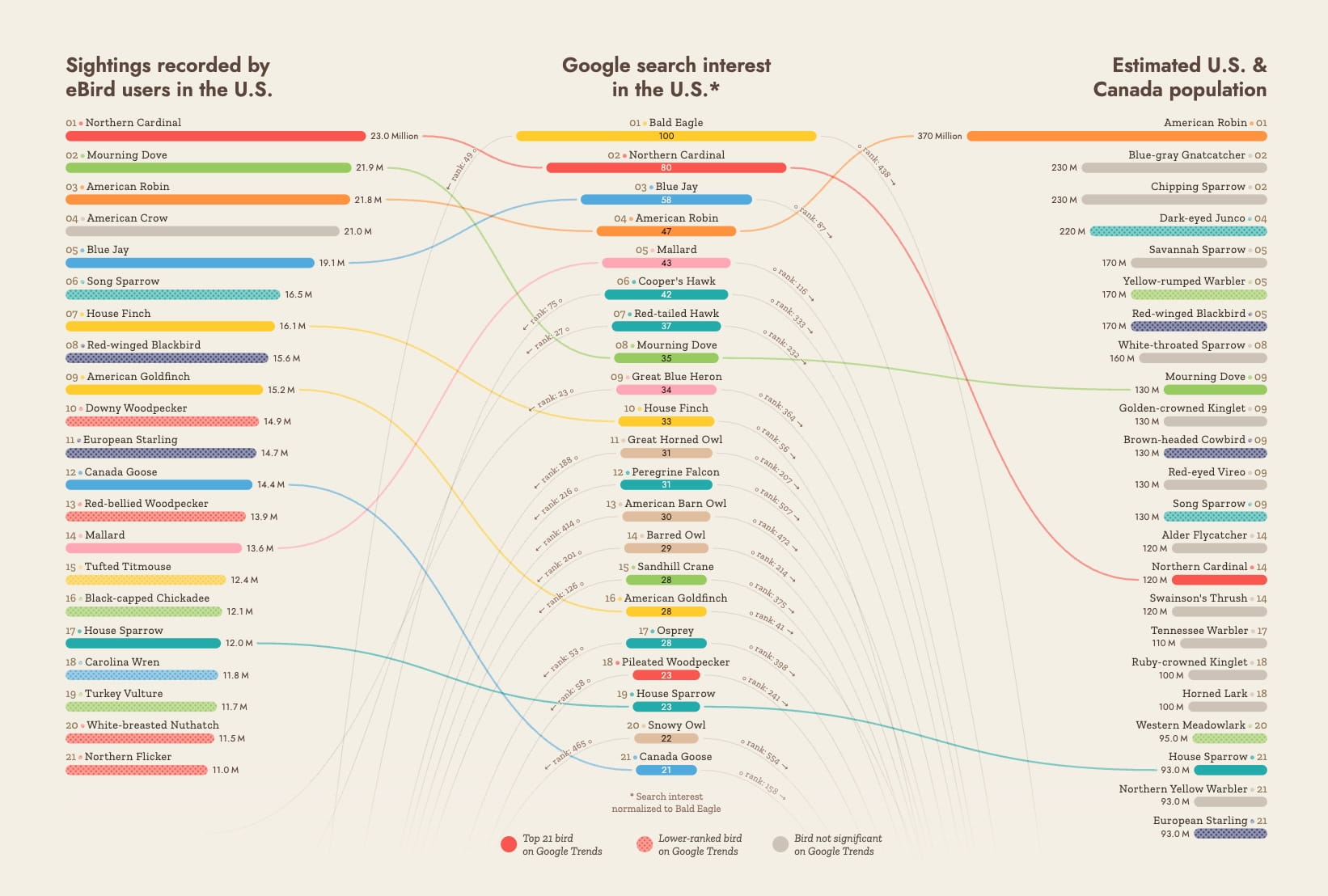

Snowy Owls are the 465th most observed species on eBird and they rank 554th for total North American population, according to Partners in Flight, which maintains an Avian Conservation Assessment database. That puts Snowy Owls toward the bottom of the list of North American birds. But, despite their obscurity, Snowy Owl is the 20th most Googled bird species in the U.S. Other elusive birds, particularly owls like the Great Horned Owl and the American Barn Owl, also make the top 20.

The chart below lists the 21 most searched birds in the U.S. (middle column) compared with eBird observations (left) and U.S. and Canada populations (right). Species with significant search interest have a colored bar. These are the same birds that were highlighted in the egg, above. (A solid color bar means the species is in Google’s top 21, and a hatched bar means it ranks lower down.)

Chart: Search Interest vs. Real World Data

A bar chart comparing three rankings of the top 21 birds: eBird Observations (what people see/report), Google Search Interest (what people search), and Population (how many exist). There is a strong correlation between sightings and searches; birds we attribute to seeing often are also searched often. However, there is a disconnect with population size; many abundant but small or elusive birds (like sparrows) are rarely searched, while rarer but iconic birds (like Eagles and Owls) are searched frequently.

Looking at the lines connecting the three lists, it’s apparent that what we spot in the wild is also what we tend to search for on Google: About half of the species on the eBird observation list (on the left) are also on the Google search list (in the middle).

Only the American Crow, No. 4 on eBird's list, doesn’t register on Google Trends. This is likely because most people search simply for crow instead of its species name.

At the same time, only four birds on the most populous list (along the right) are also on the most searched list. This is in part because many small bird species like the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher and the Savannah Sparrow are abundant but well hidden in their protected habitats, away from our eyes — and our curious minds. In fact, out of the five most populous birds in North America, three of them do not even register on Google Trends. (And we’re talking about hundreds of millions of these little feathery balls flying across the skies!)

Although we Google some rare and elusive birds like the owls, the rarest of the birds fail to spark our curiosity. Over 200 species, accounting for nearly a third of U.S. birds, need urgent conservation, according to a 2025 report published by the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, and 112 of them have lost more than 50% of their populations in the past 50 years. We don’t Google them because they exist on the fringes of our world, even though it’s these birds that most need our attention.

Part Five

Species We Know and Love

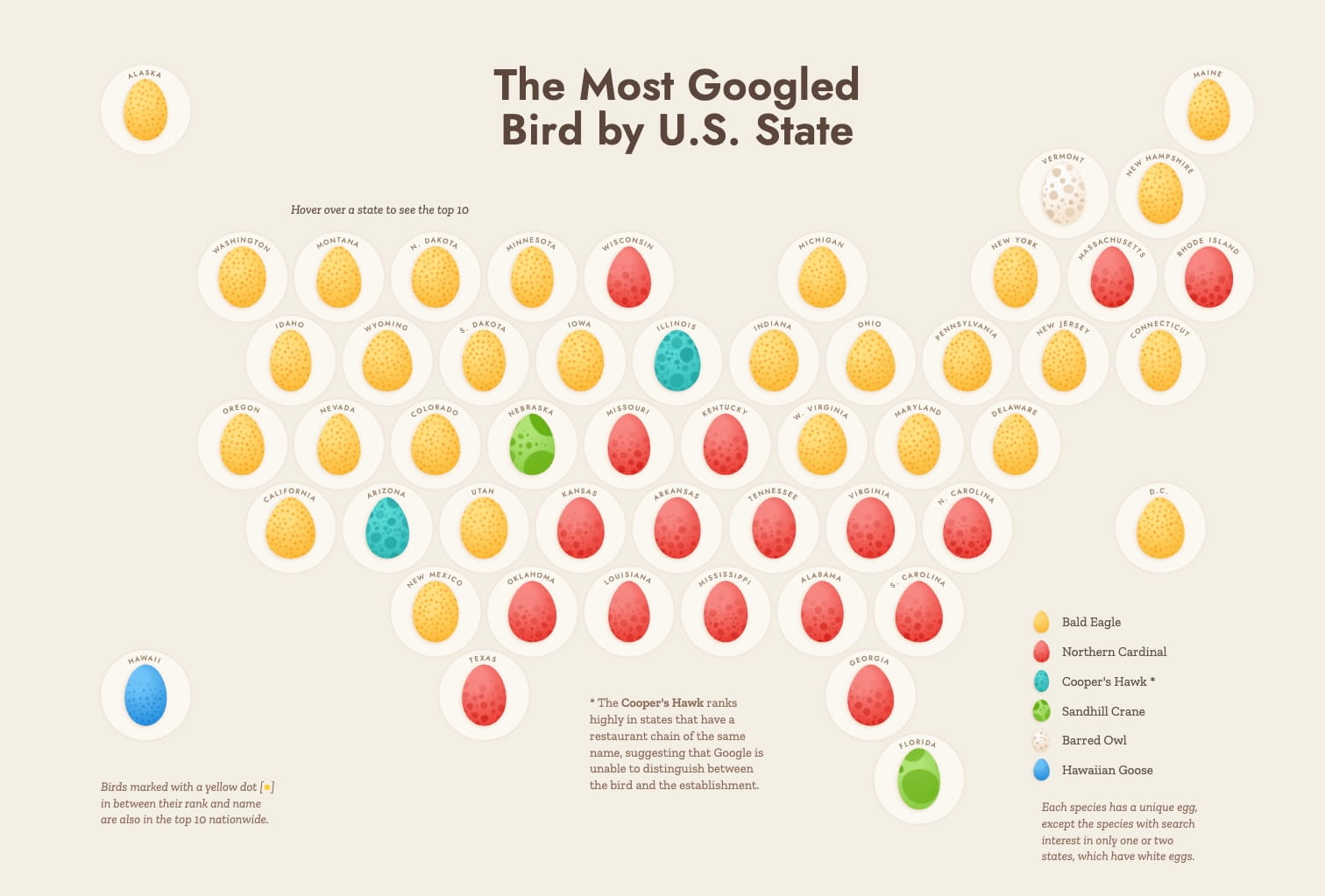

The Bald Eagle is one species that got our attention just in the nick of time. In the mid 1900s the species was nearly wiped out by habitat destruction and DDT insecticide poisoning. The species had a few things working in its favor: It is the emblem of the U.S. and it has also been meaningfully symbolic to people throughout history — from centuries of Indigenous peoples to the Founding Fathers to contemporary Americans. Through publicity and conservation efforts, Bald Eagles became an icon of the environmental movement. Today Bald Eagle is the top searched bird nationally and also in 26 U.S. states. (In the remaining states, it places second or third, except for Hawaii, the only state where it doesn’t live in the wild.)

Another bird species that many Americans know and love is the Northern Cardinal. Northern Cardinal is the second most searched species in the U.S. and the top searched species in 16 states. Its popularity no doubt stems from the males’ bright red plumage and its frequent appearances in gardens and feeders. It ranks highly in just about every state east of the Rockies, but doesn’t crack the top 10 in the western states that are outside its habitat range.

Some species, such as the Blue Jay and American Robin are highly searched in many states — which is why they are, respectively, the third and fourth ranked birds nationally — but neither has the top spot in any state.

The map below shows the most searched bird by state. Hover overSelect a state to see its top 10 species on Google Trends.

Map: Most Searched Bird by State

A hexagon tile map of the US showing the top searched bird in each state. The Bald Eagle is the most popular, claiming the top spot in 26 states. The Northern Cardinal follows, leading mostly in the East.

State-level rankings give a glimpse into what draws humans to search different birds. In Nebraska, for instance, Sandhill Crane is the most searched, likely because the North Platte River valley hosts the largest gathering in the world, with up to 600,000 cranes stopping to rest and feed for about six weeks before migrating north.[*]

In Louisiana and Mississippi, Mallard and Wood Duck are in the top five most searched, likely because duck hunting is such a popular pastime in those states’ extensive marshlands.

Cooper’s Hawk, on the other hand, is a search term that ranks highly in a few states that also happen to have a restaurant chain of the same name, suggesting that Google Trends is unable to distinguish between the bird and the establishment.

Part Six

Paying Attention

Long before social media feeds and birding apps, birders relied on analog systems to get information. Rare bird hotlines — phone numbers run by local Audubon chapters or birding clubs — catered to enthusiasts hungry for news of a vagrant warbler or storm-swept gannet. Callers would dial in, listen to a recorded message, and, if they were lucky, hear that an awesome bird had touched down nearby.

Today, news of a rare sighting travels very differently. An alert on a WhatsApp group or social media or eBird can ignite a frenzy within minutes, drawing crowds to parks and street corners with binoculars in hand. Which is exactly what happened when the Snowy Owl appeared in New York City. Word traveled fast and people who had never used a field guide suddenly wanted to know everything about this arctic wanderer. Rare bird alerts such as this routinely produce Google search spikes resulting from the rush of discovery.

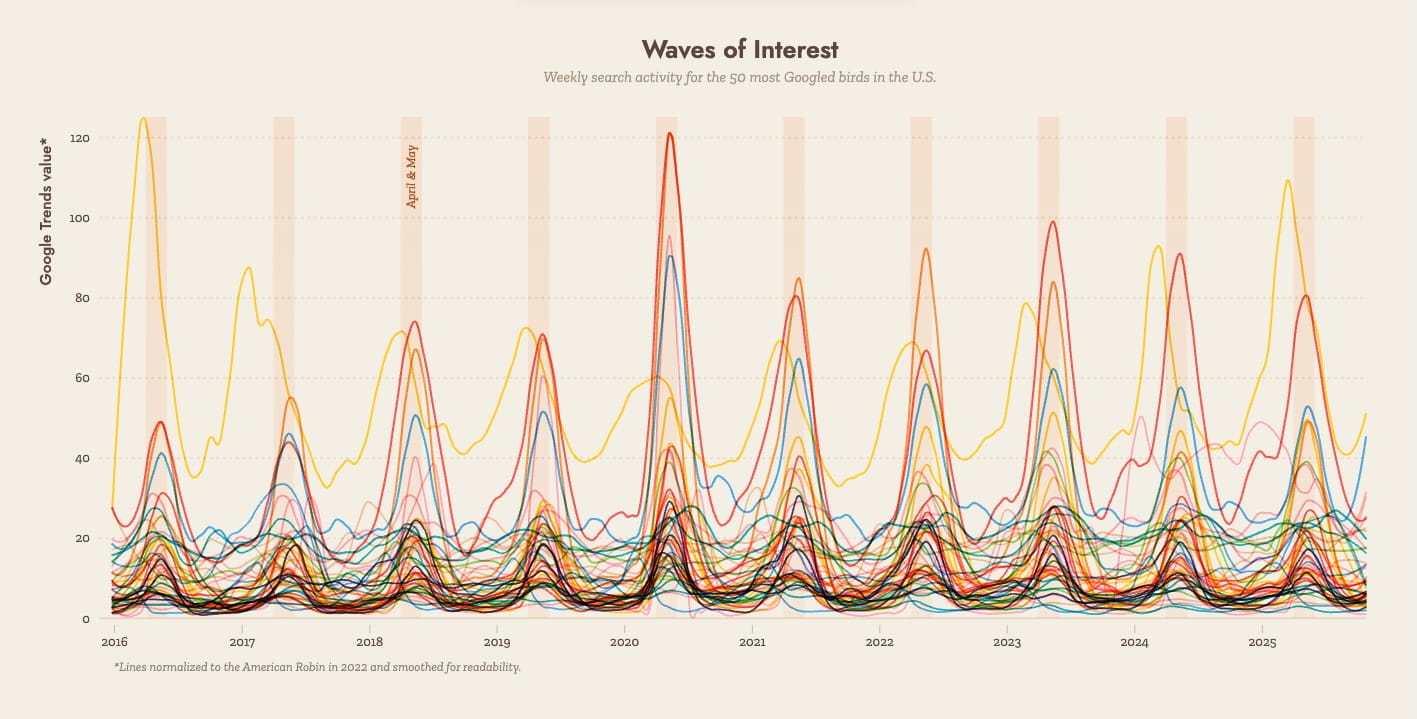

Beyond these sudden (and often localized) bursts of search activity, Googling birds follows a seasonal rhythm, as shown in the below chart of the last 10 years.

[ In case not all the years between 2016 - 2025 are visible, you can move the line chart left and right to see more years. ]

Chart: Seasonal Search Trends

A line chart showing Google search trends for birds over the last 10 years. It reveals a distinct annual pattern with search interest peaking every spring (April/May), coinciding with migration. There was a notable surge in interest during the pandemic (Spring 2020/2021).

Springtime surges

Every year there is a pronounced rise in Google searches in April and May, two major spring migration months. This is when millions of birds are on the move, budding trees make sightings easier and birdsong activity peaks. It’s also when the world feels alive again and we venture outside to notice the world around us.

Pandemic peak

That seasonal pulse was amplified during the pandemic, when search activity for bird terms rose considerably. With travel limited and daily routines stripped back, we paid closer attention to our immediate surroundings and birds became an accessible source of entertainment just outside our windows.

A bit out of line

The rhythms of bird migration and Googling vary somewhat from species to species. Bald Eagle [●] ticks up a little earlier in the year, in line with peak nesting season in February and March.

Searches for Snowy Owl [●], Snow Goose [●] and other cold weather species peak in the winter months. And searches for Common Raven [●] and Rock Pigeon [●] don’t have much seasonality at all, as these are year-round birds.

Whatever month or season it is, birds are everywhere, from the docile Mourning Doves in the grass to the predatory Peregrine Falcons on the cliffsides. Yet we often don’t even notice them, let alone search for them on Google, or on birding apps, or in field guides. Most of the time, they fade into the background of our lives.

There are many ways you can bring birds into focus into your own life, by, for instance, joining a birding community, downloading an identification app, or cracking open a birding book. But the easiest way is simply to pay attention. Once you do, birds have a way of giving back, instilling you with joy, wonder, surprise and curiosity, as the Snowy Owl did for so many New Yorkers on that cold winter day.